There were no other cars in the lot behind the borough building when I pulled in and parked. The digital clock on my dashboard glowed 2:43. I sat for a long moment, then got out of the car, hit the lock button on the key chain, and walked around the side of the building. My breath made silvery ghosts that hung in the air.

When I got to the front of the building I was looking into a single floodlight that shone on the crib scene. I put the light between me and the manger, and then I could make out the figures in the crèche. Mary and Joseph were kneeling on either side of the little crib that held the infant Jesus. He had no covers and his hands and feet were bared to the night cold. Where were His ‘swaddling clothes’ I wondered? The three wise men were kneeling, and there were two camels, a shepherd and two sheep. I said a little Christmas prayer and then I turned toward the war memorial a few feet away.

And there was Charlie.

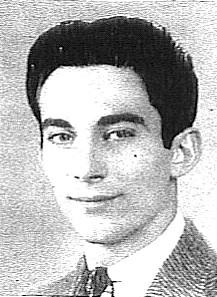

Charlie Voelker, my best friend in high school. He lived at my house during our senior year. His Mother had died, and his Dad wintered inFlorida, so Charlie had moved in with us. My Mom was his Mom, and he was still with us when we both decided to enlist in 1942. Close as we were, we didn’t join the same branch of the service. I went to the Air Corps, Charlie enlisted in the Marines. He was killed on Iwo Jima in February, 1945.

“Class of ’41 got hit pretty hard,” he said, just like that. He was studying the names on the new bronze plaque on the front of the memorial. The last time I had seen him was in the fall of 1942 when I hitch-hiked 600 miles to his Marine base, Camp Lejeune, in North Carolina. Now he stood there in that same Marine uniform, at parade rest… feet apart, hands clasped behind his back. And he spoke like there was only a comma, not a period, since the last time we talked.

“Charlie,” I said, trying to stay calm, “what are you doing here? How can you be here?”

“This brought me here,” he said, pointing to the war memorial, a massive, granite marker with a world globe on top.

‘This has been here for years, Charlie.” I stammered

“But the plaque on the front is new.” he said. “The bronze plaque with our names.”

I nodded. “It was dedicated this last Memorial Day. Took us about a year to find all these names.”

“Who is ‘us’?” he asked.

“Six ‘oldsters,’ world war two vets, and one ‘youngster’ a 49 year old guy named Mark. He convinced us this memorial didn’t give due credit. He thought the ones who died in uniform deserved special recognition.”

“That’s what brings us back,” Charlie said. “Until we get recognized by name we stay in the staging area.”

“Charlie, I don’t understand. You … you died on Iwo Jima. You were killed on the third day of the battle, 21 February, 1945.” The words came hard.

He nodded. “The day we die we go to the staging area.” He said it easily, matter of factly. “We get put back together, like we were before it happened. Even our uniforms are just like new. And then we wait.”

“You’ve been waiting more than 60 years!”

“If you say so. We don’t of keep track of time. Everything stops. I think they call it suspended animation.”

“And getting your name on this plaque sort of…. what? Breaks the spell?”

“Right, when we are individually remembered, like this.” He pointed to the names on the plaque. “This old granite memorial just says ‘Dedicated to the memory of the men and women of Crafton borough who served in the armed forces of the United States of America.’ But when you recall our names it brings us home. We get to come back and see one person from our former life before we move on permanently.”

“And you picked me?”

“Of course, buddy. No family left, and we did enlist together.” Then he asked a question that stunned me.

“Did we take that island? Did we take Iwo Jima?”

“Oh, yeah. Oh yeah, you took it alright. But it took 36 days and six thousand Marines were killed. It was the bloodiest battle in Marine history.”

“Was it worth it? The island didn’t seem very big. Took our convoy three weeks to get there from Hawaii, to this little speck of an island in the middle of nowhere.”

“Yeah, Charlie, it was worth it. Iwo was halfway between the MariannaIslands and Japan, and there were two airfields and a radar station on the island. Our B-29 bombers were flying from the Marianas to bomb Japan. Every time they approached they were picked up on radar and the Japanese scrambled their fighter planes. They got the B-29s coming and going.”

Charlie was listening intently, hanging on every word.

“After you guys secured the island there were no more fighters, and a lot of crippled B-29s got to land there coming back from Japan. Before that, they had to ditch. They figure taking Iwo Jima saved about 30,000 lives for the Air Corps.”

“Figures it would take us Marines to save you candy-ass flyboys,” he said laughing, and a little bit of ‘Charlie the class clown’ showed through.

“Another thing the battle on Iwo Jima did was to help the president decide to drop the atom bomb.”

“Roosevelt decided what?” Charlie asked.

“No, not Franklin Roosevelt. FDR died in April and Harry Truman became president. When Truman saw the fanatical defense the Japanese put up at Iwo he figured it would be even worse if we had to invade their homeland. Our troops would be fighting not just their military, but women and children.”

“Roosevelt dead? He was practically the only president we ever knew.”

“Yeah, seemed like it.”

“But what was this atom bomb?”

“It’s a super bomb. Just one of them wiped out the city of Hiroshima. Then we dropped another one on Nagasaki three days later and the Japanese surrendered. A lot of our boys heaved a big sigh of relief. The invasion of Japan was already planned for November. It even had a name, Operation Downfall.”

Charlie sat down on the ledge at the base of the monument and leaned back against the plaque. He pulled out a pack of Lucky Strikes and offered me one. I shook my head no. He reached into his pants pocket and pulled out a Zippo lighter. When he put the lighter back in his pocket he fished for a moment, then flipped a coin to me.

“That’s the lucky silver dollar your Mom gave me when I left. Has my birth year on it. You still got yours?”

“No, got lost somewhere along the way. I guess it wasn’t so lucky anyway. You know you got yourself a Purple Heart, the hard way. The Purple Heart motto is what we chose for the plaque.” I read him the words at the top of the plaque, ALL GAVE SOME, SOME GAVE ALL. “You also were awarded a Silver Star. You wiped out a Jap pillbox that had your platoon pinned down, kept firing your anti-tank rocket launcher till you ran out of ammo.”

Charlie shook his head slowly, like it was a bad memory and he didn’t want to talk about it. When he finished his cigarette he got up and snuffed it out on the instep of his shoe. Then he shredded the butt, sprinkled the tobacco around, and rolled the paper into a tiny ball. I remembered we were taught to do it that way if there wasn’t a butt can around.

He pointed a finger at the plaque. “Four of us from the class of 1941 here.” Then after a pause he said “What happened to Vince? His dad used to cut my hair.”

“When we were trying to get these names a lot of families provided information. Vince Scafoglio was Navy. His destroyer, the U.S.S. Johnston, was sunk in the Philippine Sea in October of 1944. Vince survived the sinking….” I paused and took a deep breath, “but then sharks got him. His Mother never recovered.”

“Is the barber shop still over there?” Joe Scafoglio’s barber shop had been less than a block from where we were.

“Long gone,” I said.

“How about Cappy?” Charlie asked.

“Joe Capebianco. Little guy, flew big transport airplanes. Killed in a plane crash.”

“Len?”

“Leonard Wood. Graduated West Point in three years, and then took flight training. His P-47 fighter got away from him on takeoff on Okinawa. His wife was pregnant at the time, and he had a son born four months after the accident. Len Junior was born right here inPittsburgh. He’s 60 now, lives in Alaska, but he came down for the dedication of this plaque.”

“Len will be seeing his son for the first time,” Charlie mused. “His 60 year old ‘baby.'” Charlie sat down on the base of the memorial and leaned back against the plaque. “It’s nice to be home,” he said.

“That’s the feeling all of us have, that we brought you home. It just didn’t seem right to leave you in those God forsaken places, thousand of miles from here.” I sat down beside him.

“Remember when we used to take those Sunday drives in your Model A Ford? We would go to Chester, West Virginia, Steubenville, Ohio, and back to Pittsburgh. Almost 100 miles and three states in one day! We felt like real hot shots. Then you get killed on an island 9,000 miles away.”

I wanted to change the subject. “You remember what that Model A cost?”

“Sure,” he said. “It was $35. Took me three months to pay it off.”

“You know you can’t fill your gas tank for $35 today?”

“You’re kidding!”

“No, and that pack of cigarettes you have costs about $4 now.”

And we were on a roll, reminiscing about the thirties and early forties. We talked about our high school girl friends and our high school teachers. It was hard for him to think of them as being old now, or gone.

We talked — mostly I talked — about television, computers, cell phones, the space shuttles, landing on the moon, the Hubble telescope. It had been the most remarkable period in history, and I was in awe of it too as I reviewed it all. Now and again the old Charlie would burst out with his familiar laugh, but not often. He was still 22, but he was a much older 22 than the just-out-of -high-school kid who had marched off to war. We talked till it was almost dawn, and the sky was turning plum blue. Charlie stood up, turned and gave me a hand.

“Will I be seeing you again?”

He looked at me with sad brown eyes and nodded.

“Good,” I said. “When will you be coming back?”

“I won’t be coming back,” Charlie said softly.

It took a while to sink in, and then I said, “No complaints. I’ve had a heluva ride. And I get to leave seven grand kids to carry on.”

A light snow started to fall as Charlie walked over to the crib scene and stood looking at it quietly. Then he took off his uniform jacket, laid it gently on the infant Jesus and tucked it in all around, first on the sides, then at the feet.

“You’re out of uniform, soldier.” It was all I could think of to say.

“Isn’t it about time?” Charlie said. And then he was gone.

I woke up slowly, and the events of the night were spinning in my mind. I went to the back window and my car was there in the carport. But there were no tracks in the snow on the driveway. Did it all happen, or did I just dream it? It was so real. I went back to the bedroom and mulled it over as I dressed. I buckled my belt and started to put the things on the dresser into my pants pockets. Comb, credit cards, car keys, some folded bills, and the change. And there it was, much bigger than the other coins. A worn silver dollar. I stared at it for a while, then picked it up and looked at the date. The date was 1923, the year Charlie was born.

EPILOGUE

While my best friend, Charlie, trained for the amphibious assault on Iwo Jima, I was going through Air Corps flight training. On the day he hit the beach, February 19, 1945, I was flying over Germany on my 52nd mission, piloting the lead aircraft of an 18-plane formation of twin-engine Martin B-26 Marauders.

The citation for Charlie’s Silver Star reads, “When his company’s assault across the beach was halted by a hail of fire from a hostile force in a pillbox, Corporal Voelker boldly crawled out in advance of his platoon and, ignoring the small-arms fire concentrating on him, pressed forward relentlessly to a position where he could bring fire to bear on the emplacement with his anti-tank rocket launcher. He destroyed the strong point before he was fatally wounded after expending his last shell.”

When the war in Europe ended I had flown 71 missions, always lucky enough to be at least a wing span from disaster. I had been awarded a Distinguished Flying Cross, the Air Medal with eight oak leaf clusters, and no Purple Heart.

I came home to a hero’s welcome. Charlie was laid to rest under a white cross on Iwo Jima.

Chuck O’Mahony, ‘41

Crafton, PA